his week's Thursday feature is an interview with Katie Garcia, the founder and president of Athene Strategies, a strategic and crisis communications consulting firm. I asked Katie a series of questions about an important topic for any fundraiser, how to communicate with your constituents during an organizational crisis. 1) When a non-profit organization finds that it is in the midst of a crisis, what is the first steps that the staff should take? The first step that an organization needs to make when in a crisis is to recognize that a crisis is occurring. When people think of crises, often times they think of the effects of poorly handled crises – they think of organization disasters. But a crisis is not necessarily a disaster. A crisis is a time when an organization is unable to operate normally. When handled poorly, a crisis can lead to a loss of trust and confidence in those who matter most and cause reputational harm. But when handled in a timely and effective way, a crisis can actually become an opportunity to gain competitive advantage, to build trust and confidence, and move the organization forward in achieving its goals. So the first step is to recognize when an organization is or will soon not operating normally. The second step is to clearly identify what the crisis is. Crises are organizational problems, not simply communication problems. Communication in and of itself is not enough to end a crisis. (Communication can exacerbate a crisis or organizational problem though). If you do not identify where the actual problem lies, you will not be able to respond in a way that will effectively end the crisis. Therefore, you need to clearly identify what the organizational problem is before you respond to the crisis. The third step is to decide how to respond to the crisis by asking and answering the following question: What would reasonable people appropriately expect a responsible organization to do when faced with this? This question is important. It is not asking what it is that an organization wants to say. That is self-indulgent. And while it might make an organization feel good, it will not move those who matter most to continue to support with the organization. Rather, the right question focuses on what the people who matter most – an organization’s stakeholders – would reasonably expect a responsible organization to do. And if an organization asks and answers this question, and then responds based on that answer in a timely way, an organization can end the crisis, increase trust and confidence in the organization, and get back to operating normally. 2) Is there any difference in how you handle a controversy versus a crisis with respect to communication? A controversy may or may not become a crisis. A controversy is a matter of public dispute, debate or disagreement. If a controversy gets to the point where the organization can no longer operate normally, then the response would be the same as for a crisis—to ask and answer the question: What would reasonable people appropriate expect a responsible organization to do when faced with this? And depending on what the crisis is, the response will differ based on the answer to that question. But the process is the same as with every crisis. However, a controversy may not become a crisis. For example, in a university setting, a dispute over hiring a professor because of their identity or a change in a tuition model are not crises. In that case, a controversy could be an opportunity to showcase the mission, values, and work of the organization in a way that reaches a larger audience than the organization would otherwise be able to reach. But to do that effectively, an organization would need to think strategically about 1) what it wants to achieve; 2) who the organization needs to reach to achieve that goal; and 3) what the organization wants that audience to think, feel, know or do in order to help achieve that goal. 3) What's your advice for fundraising during a crisis? Fundraising during a crisis needs approached in a strategic way. Whether or not and how to fundraise during a crisis will depend on what the crisis is and how the organization is responding to it. Sometimes, it may not be appropriate to fundraise during the crisis itself. For example, if the crisis revolves around an accusation that leadership have unethically or illegally handled their organization’s finances, fundraising before the crisis is resolved may not be appropriate and can actually exacerbate the crisis. Other times fundraising could be part of or support the crisis response. For example, if there is a natural disaster that affects those an organization serves or where the organization operates from, it could be that the organization fundraises specifically to address that need. When figuring out if and how to fundraise during a crisis, it will go back to the question of: What would reasonable people appropriately expect a responsible organization to do when faced with this? Fundraising during a crisis should be done in ways that are consistent with or in support of the crisis response and are appropriate given the circumstances of the crisis. 4) What are the best signs that the crisis is over? The key indication that a crisis is over is that the organization goes back to operating normally. If the crisis is handled well, that moment could happen right after the initial response. If an organization responds effectively right at the beginning, then the crisis may end before it really begins. The best handled crises are the ones that no one, outside the response team, knows about or noticed. But if the crisis is not handled well or in a timely enough way, or if the response involves some sort of shift within the organization – whether it be in personnel, leadership, or processes – it will likely take more time to get back to operating normally. And normal operations after the crisis may be different than what it was before the crisis. 5) What are your 3 favorite tips for handling the communication during a crisis? 1.) Take a deep breath and a step back. It is difficult when an organization you have devoted yourself to is in crisis. As human beings, it is in our nature to respond emotionally first when faced with a crisis. Whether it be with anger, confusion, sadness, panic, disbelief, denial – whatever you may be feeling, take a deep breath. And then another one. Find a way to stay calm. You will not be able to think clearly or respond effectively if you become consumed in your own feelings about what is happening. And then take a step back. Look objectively at the situation. See the whole board. Only then will you be prepared to respond to the crisis. 2.) Remember that leadership is not about you, it’s about who you serve. Leaders are charged with making decisions for the good of the organization. Sometimes that means doing or saying things that you may not be comfortable with or may not want to say or do. During a crisis, it is only too easy to get stuck in focusing or making decisions based on what you want to do, rather than what you need to do to fulfill the reasonable expectations of those who matter most to the organization. Remember when responding to a crisis that it is not about you or what you want – it is about your stakeholders. Leaders need to overcome the fear and inertia that leads to inaction in order to respond in timely and effective ways. 3.) Learn from past experience. We need to learn from past experience, both your own experience and the experience of others. In terms of crises, we can open any newspaper or watch any news program to witness what other organizations in crisis have done – decisions that either led to a crisis or decisions in how the organization responded to a crisis. Learn from these examples. They can guide you and organization as you answer that question of what reasonable people would appropriately expect a responsible organization to do when faced with this. What works for one organization may not work for another, but you can learn from other organizations. And in your own life, learn from your own experiences of facing crises. Learn from past crises in your life and the organization. What worked? What didn’t work? What could you or the organization have done differently? Let those past examples also guide you as you encounter crises or potential crises in your organization so that you can respond in timely and effective ways. More about Katie Garcia: Katie Garcia is the founder and president of Athene Strategies, a strategic and crisis communications consulting firm. For more than 10 years, Ms. Garcia has worked in the field of strategic and crisis communication and leadership development. During this time, she has advised leaders and organizations across multiple sectors including non-profits, international and national NGOs, religious institutions, educational institutions, political action campaigns, inter-governmental organizations, and small businesses. Ms. Garcia has trained and advised leaders and emerging leaders across sectors to improve their ability to communicate effectively in their positions of leadership. Prior to founding her firm, she served as Interim Communication Consultant for the Starr King School for the Ministry and Communications Consultant for Religions for Peace. She has also worked in organizations such as Freedom to Marry, Disaster Chaplaincy Services, and Logos Consulting Group. Hi! It's Jessica. I draw on the concepts that Katie presents in this article in my webinar presentation titled Fundraising in a Crisis. This webinar will launch Wednesday 3/18/20 for free as a resource for nonprofits to respond to the COVID-19 crisis. You can register here: www.realdealfundraising.com/crisiswebinar. There are a lot of ways to get these two terms muddled together and confused. Having worked at large state-supported universities for most of my career, I'm guilty of using the terms "annual fund" and "annual giving" interchangeably.

Here's the crucial difference: some institutions need unrestricted funding in order to make their operating budget and provide basic services to meet their mission. They have an annual fund, which is unrestricted. And while these organizations accept and appreciate designated gifts to programs and named funds, they still require a certain amount of unrestricted giving. There is a laser focus on unrestricted giving. The pitch is all about the importance and uniqueness of that organization's mission in our world. The need for support is tied to the worthiness of the institution itself. Other organizations just want loyal donors to make a gift of any level, every year. This is annual giving. Usually, it is not fund specific. For instance, at most large universities, the goal of the office of annual giving is to boost alumni participation rates and the ability to designate that gift to a niche department, program or scholarship is part of the pitch. Why would an institution that doesn't need operating dollars run an annual campaign? There are many reasons but here are a few:

I now work for an institution that needs operating dollars and "annual fund" doesn't just mean "small gift amounts". Major donors play a big role in helping our organization to meet our goals. I had to completely clarify in my mind the differences between raising money for the "margin of excellence" versus raising money to meet our budget. Unrestricted giving isn't value-add at many small non-profits and smaller institutions of higher education; it is a necessity. Deeply understanding that there are two very different approaches to annual fund/giving is essential if we are to communication effectively with our colleagues at other institutions. Make sure to ask questions about whether the annual fund is unrestricted giving only, whether it includes major gifts and whether your goals are calculated by what you can raise or by your budgetary needs. Finding a colleague at a similar institution is helpful if you are hoping to craft a perfect pitch for your annual campaign. Do you work for an annual fund institution or an annual giving institution? Writing a fundraising letter is tough. Making it sound original and compelling is even tougher. Sometimes you can become stuck, too afraid of writing something that is stale and boring to get anything done. If this sounds like you, you have DMWB: Direct Mail Writer's Block.

Here's 5 steps you can take in about half an hour to break through your writer's block and get a draft completed ASAP: Step 1: Understand that some words are better than no words. The most important thing about fundraising is THAT you ask. Sending some mediocre letters out will generate more money than sending zero perfect letters out. Once you realize this, it is a liberating feeling. Something is better than nothing. So, don't worry so much about it being super-compelling and perfect at this point. Step 2: Find a white board (preferably a big one) On the top of this whiteboard, write what you are raising money for. This might be "OPERATING FUNDS" or "SCHOLARSHIPS" or something else. Now go one level deeper and take that (in just a few words) to what it means for people. How will lives be changed because of raising money for this designation. So, it might say, "Funds to allow more students to study abroad", "more meals for the homeless" or "students able to graduate with less debt". Next, you need to make a short list of 3-5 possible signatories for your letter. Do this step even when you think you've already decided who will sign it. Sometimes a traditional "dean's letter" or "president's letter" isn't the way to go. The best letters I've ever written were signed by students, the recipients of the support. Step 3: Generate reasons to give Add a list of 3 EMOTIONAL reasons that your constituents should want to give and 3 ANALYTICAL reasons that they should give. You need a mix of both of these. Most people tend toward one or the other. For example, I'm wholly analytical. I like to know things like the percentage of the cost of an education that's covered by tuition. I like to know about challenge grants and alumni giving percentages and whatnot. The data makes a rational argument to my mind and that style is much easier for me to write. If you are like me, you're not great at coming up with the emotional reasons to give, but an exercise like this forces you to work with both kinds of case making. The emotional reasons usually include a story of a grateful recipient of the support and can include nostalgia for the organization or pride in past work that the donor participated in. Step 4: Evaluate Based on what you see on your whiteboard so far, can you take the story or voice of one of those possible signatories and work in several of the analytical AND emotional reasons to give in one letter? (If yes, go to Step 5.) If no, return to the top of your whiteboard. Do you need to re-address what you’re fundraising for or do you need signatories with more authority or better personal stories? Step 5: Write without self-censoring At this point in the process, you have a focus for your pitch (your designation), a signatory, emotional reasons to give, and analytical reasons to give. Now, get out of your own way and WRITE, without self-censoring. Don't judge. Just get enough text down in written form. Later, with the magic of cut and paste, you can remove, move and juggle all the juicy bits of language. But you can't get to that point until you generate all the phrases and sentences. Don't forget to think about customizing the language for your different segments along the way. This is the best method I've used for snapping out of a direct mail writer's block: get your psychology straight, focus on what you are raising money for, the reasons to give and how that matches with who should sign the letter. Then get out of your own way and get it all down in words. Happy writing! If you try this, let me know how it works out for you. Giving donors reasons to give is an important part of case-building. Don’t underestimate the simple power of a top ten list. Here is a list of ten possible reasons to give to get you started brain-storming your own reasons to give at your institution.

You can create a dedicated webpage out of these and then promote one per week or day on social media and then repeatedly re-post the website. Make sure your text explaining each of these reasons has links to your giving page. #10: Tuition is not enough. Tuition usually only covers a portion of the cost of an education. See if you can use this reason to give to present this data. Emotional appeals are great for many donors but others want to see the numbers and facts. #9: Open doors of opportunity. Community support is critical to helping hard-working students graduate. Many of your students could not afford an education without scholarship assistance. Make that case with this reason to give. #8: Invest in today’s students, tomorrow’s leaders. A gift to your institution helps to clear a path to a degree for many students. Perhaps quickly mention a story of what one of your recent graduates is doing that is impressive and noteworthy. #7: Gifts help your institution attract major gifts and grants. Foundations and corporations often consider charitable support to be an indication of merit. For example, they may look at the percent of alumni giving, the percent of employee giving and the total dollars raised each year when evaluating a grant application. A gift sends a signal to these outside funders that your institution is worthy of their support. #6: Maintain the value of a degree from your institution. Giving, as we know, is key factor considered by accrediting agencies and ranking institutions like U.S. News and World Report. It’s important to communicate to our constituents that especially if you are a graduate, your gift will help the institution maintain accreditation and increase its reputation, thereby increasing the value of a degree from your institution. Even a small gift makes a difference. #5: It doesn’t take much! Your gift, combined with the gifts of others, can have a very powerful impact, regardless of the amount. No gift is too small to make a difference! Together we can reach our goals but we need your participation. #4: It’s a worthy tradition. Your institution has been educating people since its year of founding and it is likely that your institution has been sustained by generous gifts at every step along the way. It is vital that today your alumni and friends carry on this important tradition of generosity. #3: Amplify your values. When you give to your institution, you are giving to students who are also future leaders. What do you students do when they leave your institution that is unique and valuable? Whose lives will your students change? #2: The world needs your institution. For this reason to give you will really needs to dig into what makes your institution unique among other institutions. What do you offer the world that no one else can? #1: Now is the time… Make an investment in your institution so that it can expand its mission. Explain why your institution is unique and precious and that the time is now to make a gift which will be tangible evidence of the hope we all share for how this institution can change the world.  The concept of "grateful patient" fundraising has always fascinated me. How meaningful, how wonderful, how . . . . EASY to raise money from those who lives were saved by your institution! A team of specialists at your hospital saved someone's child from cancer and they have capacity. What a wonderful story! Of course, I know that it isn't that simple to raise money in healthcare fundraising. But, the stories of grateful patients are enticing and make those of us in higher education a bit jealous. Unfortunately, most stories are a bit less tangible than that in higher education. No matter what kind of organization you work for, I find it is a great exercise to reflect regularly on the question, "Who are your grateful patients?" Asking this questions drives you right to the core of your mission. Who is served by your institution? How does it change lives? These questions takes you deep into impact and narrative. This question leads you to the "Why?" In higher education, who are our grateful patients? Last week, I was composing a blog post about how philanthropic support has directly helped me in my life and career. We often think of students as our grateful patients and they are. But, more than that, it is our ALUMNI that are the grateful patients. Students who graduate and move out into the world changed by the education they acquired at our institutions. The stories of students work to connect our alumni to mission only if those stories activate the sense of gratitude that our alumni have for their own time at our colleges and universities. It's not mere nostalgia, it is a real and tangible linking back that our student narratives must do in order to invigorate the "grateful patient" sensibility of our alumni. They must see in the story of current students their own story and from there be able to project what their life might be like if their educational story was different. The phrase "make a difference" is overused and trite. However, if you want to find your grateful patients (who will be not only your best donors but your most enthusiastic advocates), you have dive into the real meaning of that phrase. How is someone's life path qualitatively different because your institution exists? I’ve talked about finding the stories of impact and sharing them with your donors. The importance of letting donors see how their gifts have transformed lives cannot be overstated.

Upon reflection, I realized that I have overlooked throughout my entire career, one very important story: my own. I have searched for the stories of scholarship recipients at every institution I’ve worked for and totally forgot to be recognize the impact donors have had on my own journey. I was lucky enough to have been awarded a 4-year leadership scholarship which covered my room and board at my alma mater, The University of Southern Mississippi, but I was also the recipient of a generous scholarship so that I could go to London one summer for study abroad. The Dean of the Honors College also sent me on two trips (one to Princeton and one to Washington, D.C.) using funds that I now know must have been generated from Annual Fund gifts. I also know that charitable donations helped to support the fantastic Honors Forum series that brought the most incredible scholars and public intellectuals to Hattiesburg, Mississippi. Here are some experiences that I have been able to have because I received scholarship support:

With sincere thanks, Jessica Cloud A solid strategic plan is not an easy thing to write. Ideally, it should have a balance of big picture thinking and sufficient detail so that it can be implemented. A strategic plan cannot be pie-in-the-sky but it also cannot be a user’s manual full of which button to push.

I would advise that strategic planning begin with 3 steps:

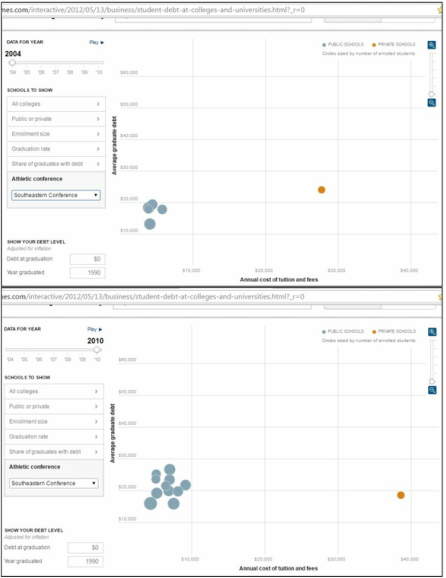

Do you have staff and budget to promote planned giving opportunities? What can you afford to do in terms of direct mail, phonathon, donor relations, etc.? Don’t forget about crucial areas like stewardship and fulfillment (pledge follow up). Also, pay special attention to data integrity and enrichment. You cannot afford to ignore those important areas. Now, you have to combine your various vehicles for communication with the content: the case for support. What will you be focusing on this year? What are the needs of your institution? Scholarships? Program support? Operating expenses? What’s the impact that the donor will have in the world if they make a gift this year? Begin to weave these messages into thoughts about how to segment your data this year. The final part of your strategic part is to have a calendar. You know enough now to lay out the steps. Don’t go into too much detail but have a month-by-month list of what major action steps need to happen to accomplish your goals. Review this calendar regularly at staff meetings. It is inevitable that you won’t get to all your great ideas in one year. I’ve found it helpful to add a section at the end of my plan called “And Beyond” where I can stash my great ideas for future years. It keeps me inspired and helps me not to forget. Encourage other staff to join you in adding to that list throughout the year. Most importantly, the strategic plan cannot be a lifeless document. If you aren’t referencing it at least once a month (preferably more), it isn't working for you. Start over. Make it a living document that guides you to your goals.  For those of us working in higher education fundraising, the issue of student debt has an increasing amount of relevance. The Project on Student Debt through the Institute for College Access and Success writes, “Over the last decade—from 2004 to 2014—the share of graduates with debt rose modestly (from 65% to 69%) while average debt at graduation rose at more than twice the rate of inflation.” How can we expect our young alumni to give back to our institutions when they can barely make their loan payments? Many in society are questioning whether a college education is good investment and the view of college is shifting to one that is transactional, rather than transformational. Not only should advancement professionals stay up-to-speed on these issues because of how it may affect the way young alumni give (or don’t give), but we should also utilize this as an opportunity to put out positive messages about how philanthropy can mitigate this situation for scholarship recipients. There are great resources available that track this information. The organization cited above (The Project on Student Debt) collects data from most colleges and universities and reports it online. You can access overall statistics, historical trends as well as data by state and by institution. With a little bit of research time, you can learn how your institution compares with peer institutions and with other institutions in your state. You can also see how the trends have change over time. The historical reports are a bit more difficult to find so here are links to the reports for 2011, 2012 and 2013. 2011: http://ticas.org/content/pub/student-debt-and-class-2011 2012: http://ticas.org/content/pub/student-debt-and-class-2012 2013: http://ticas.org/sites/default/files/legacy/fckfiles/pub/classof2013.pdf Another great resource for geeks like me is this interactive graph from the New York Times. I love this resource because it lets you see how the trends with student debt change across time and you can see how the cost of tuition has risen. You can break it down by all different kinds of criteria. For instance, here’s the some data for the Southeastern Athletic Conference for 2004 (top graph): Notice how low nearly all of the schools are in terms of both cost and student debt (blue dots). The only outlier is Vanderbilt (orange dot), which had slightly higher debt loads but was much more expensive. The expense is not surprising since it’s the only private school in the SEC. Now take a look at the 2nd graph. It’s the same data for the same schools 6 years later. At the University of Georgia in 2004, the annual tuition was only a bit more than $4,000 and the student debt was around $13,000. By 2010, tuition at UGA was over $7,500 and the average amount of student debt was now almost $16,000. There’s a totally different story at Vandy and it’s completely counterintuitive. In 2004, the average Vandy grad carried over $24,000 in student loans. The cost of an education was almost $28,000. The cost to attend Vandy rose to over $38,000 in 2010, but the average amount of student debt DECREASED to $18,600. How could this be? The answer is obvious: philanthropy. Vandy must have raised and awarded more scholarship during this 6-year period. So, charitable giving can make a marked difference in the future of an average student where debt is concerned. Why are we not writing this into each single phonathon script and direct mail piece that we produce in higher education fundraising? I encourage you to play around with these tools and do some research into the trends at your own institution. You can then build statistically relevant objection responses for alumni who say they cannot give due to student loan debt loads and more importantly you can more effectively market the potential positive impact that major donors can have when they make a gift for scholarships. |

Jessica Cloud, CFREI've been called the Tasmanian Devil of fundraising and I'm here to talk shop with you. Archives

June 2024

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed